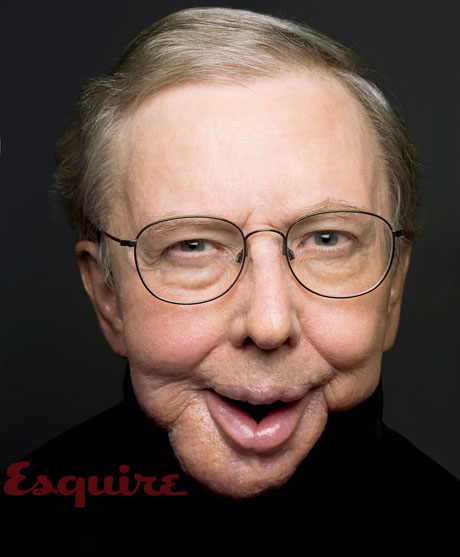

Roger Ebert, 67, is the legendary film critic of the Chicago Sun Times. I remember him from Siskel & Ebert, the long-running movie review show in which the tall skinny guy and the heavy-set man argued the merits of the latest films. Since 2006, Ebert has been unable to speak or eat following several operations to remove thyroid cancer and subsequently his salivary glands. He’s still writing, though, and keeps a blog along with formally reviewing the latest films. All he can do is write, it’s his only way to communicate, but he’s so skilled at it that if you only read his reviews you wouldn’t guess how much his life has changed.

Esquire has a very moving, long profile of Ebert and his rise to prominence along with the difficulties he faces daily. We have some excerpts below, but if you have some time I would highly recommend reading the entire article. No matter how familiar you are with Ebert’s work and personal history, you’ll get something out of this article. It’s hard to explain how it touched me, but I came away with an appreciation for life and for it’s setbacks and complexities that honestly made me feel content, like a better person. Most of that was in the form of Ebert’s own quoted words on how he’s facing his illness and death with a kind of quiet conviction that recognizes the joy in what he’s done and the opportunities he still has.

On his text-to-speech application

Ebert is waiting for a Scottish company called CereProc to give him some of his former voice back. He found it on the Internet, where he spends a lot of his time. CereProc tailors text-to-speech software for voiceless customers so that they don’t all have to sound like Stephen Hawking. They have catalog voices — Heather, Katherine, Sarah, and Sue — with regional Scottish accents, but they will also custom-build software for clients who had the foresight to record their voices at length before they lost them. Ebert spent all those years on TV, and he also recorded four or five DVD commentaries in crystal-clear digital audio. The average English-speaking person will use about two thousand different words over the course of a given day. CereProc is mining Ebert’s TV tapes and DVD commentaries for those words, and the words it cannot find, it will piece together syllable by syllable. When CereProc finishes its work, Roger Ebert won’t sound exactly like Roger Ebert again, but he will sound more like him than Alex does. There might be moments, when he calls for Chaz from another room or tells her that he loves her and says goodnight — he’s a night owl; she prefers mornings — when they both might be able to close their eyes and pretend that everything is as it was.Regaining his “voice” through blogging

There are places where Ebert exists as the Ebert he remembers. In 2008, when he was in the middle of his worst battles and wouldn’t be able to make the trip to Champaign-Urbana for Ebertfest — really, his annual spring festival of films he just plain likes — he began writing an online journal. Reading it from its beginning is like watching an Aztec pyramid being built. At first, it’s just a vessel for him to apologize to his fans for not being downstate. The original entries are short updates about his life and health and a few of his heart’s wishes. Postcards and pebbles. They’re followed by a smattering of Welcomes to Cyberspace. But slowly the journal picks up steam, as Ebert’s strength and confidence and audience grow. You are the readers I have dreamed of, he writes. He is emboldened. He begins to write about more than movies; in fact, it sometimes seems as though he’d rather write about anything other than movies. The existence of an afterlife, the beauty of a full bookshelf, his liberalism and atheism and alcoholism, the health-care debate, Darwin, memories of departed friends and fights won and lost — more than five hundred thousand words of inner monologue have poured out of him, five hundred thousand words that probably wouldn’t exist had he kept his other voice. Now some of his entries have thousands of comments, each of which he vets personally and to which he will often respond. It has become his life’s work, building and maintaining this massive monument to written debate — argument is encouraged, so long as it’s civil — and he spends several hours each night reclined in his chair, tending to his online oasis by lamplight. Out there, his voice is still his voice — not a reasonable facsimile of it, but his.“It is saving me,” he says through his speakers.

He calls up a journal entry to elaborate, because it’s more efficient and time is precious:

When I am writing my problems become invisible and I am the same person I always was. All is well. I am as I should be…

Remaining positive and appreciating the abilities he has

Even the simplest expressions take on higher power here. Now his thumbs have become more than a trademark; they’re an essential means for Ebert to communicate. He falls into a coughing fit, but he gives his thumbs-up, meaning he’s okay. Thumbs-down would have meant he needed someone to call his full-time nurse, Millie, a spectral presence in the house.Millie has premonitions. She sees ghosts. Sometimes she wakes in the night screaming — so vivid are her dreams.

Ebert’s dreams are happier. Never yet a dream where I can’t talk, he writes on another Post-it note, peeling it off the top of the blue stack. Sometimes I discover — oh, I see! I CAN talk! I just forget to do it.

In his dreams, his voice has never left. In his dreams, he can get out everything he didn’t get out during his waking hours: the thoughts that get trapped in paperless corners, the jokes he wanted to tell, the nuanced stories he can’t quite relate. In his dreams, he yells and chatters and whispers and exclaims. In his dreams, he’s never had cancer. In his dreams, he is whole.

These things come to us, they don’t come from us, he writes about his cancer, about sickness, on another Post-it note. Dreams come from us.

We have a habit of turning sentimental about celebrities who are struck down — Muhammad Ali, Christopher Reeve — transforming them into mystics; still, it’s almost impossible to sit beside Roger Ebert, lifting blue Post-it notes from his silk fingertips, and not feel as though he’s become something more than he was. He has those hands. And his wide and expressive eyes, despite everything, are almost always smiling.

There is no need to pity me, he writes on a scrap of paper one afternoon after someone parting looks at him a little sadly. Look how happy I am.

In fact, because he’s missing sections of his jaw, and because he’s lost some of the engineering behind his face, Ebert can’t really do anything but smile. It really does take more muscles to frown, and he doesn’t have those muscles anymore…

On how he plans to face death

His doctors would like to try one more operation, would like one more chance to reclaim what cancer took from him, to restore his voice. Chaz would like him to try once more, too. But Ebert has refused. Even if the cancer comes back, he will probably decline significant intervention. The last surgery was his worst, and it did him more harm than good. Asked about the possibility of more surgery, he shakes his head and types before pressing the button.“Over and out,” the voice says.

Ebert is dying in increments, and he is aware of it.

I know it is coming, and I do not fear it, because I believe there is nothing on the other side of death to fear, he writes in a journal entry titled “Go Gently into That Good Night.” I hope to be spared as much pain as possible on the approach path. I was perfectly content before I was born, and I think of death as the same state. What I am grateful for is the gift of intelligence, and for life, love, wonder, and laughter. You can’t say it wasn’t interesting. My lifetime’s memories are what I have brought home from the trip. I will require them for eternity no more than that little souvenir of the Eiffel Tower I brought home from Paris.

There has been no death-row conversion. He has not found God. He has been beaten in some ways. But his other senses have picked up since he lost his sense of taste. He has tuned better into life. Some things aren’t as important as they once were; some things are more important than ever. He has built for himself a new kind of universe. Roger Ebert is no mystic, but he knows things we don’t know.

I believe that if, at the end of it all, according to our abilities, we have done something to make others a little happier, and something to make ourselves a little happier, that is about the best we can do. To make others less happy is a crime. To make ourselves unhappy is where all crime starts. We must try to contribute joy to the world. That is true no matter what our problems, our health, our circumstances. We must try. I didn’t always know this, and am happy I lived long enough to find it out.

[From Esquire]

Without waxing too philosophical about this wonderful article and this talented man, let me just say that this was without a doubt the most touching article I’ve reported on since starting this blog four years ago. Yet “touching” doesn’t begin to capture the way it moved me. We’ve all faced challenges and setbacks in our lives and some of us have either been disabled or will face disability. I pray that if and when my times comes I can manage my life and outlook with half as much grace, dignity and humor as Mr. Ebert.

Thank you for posting this CB and for your short and insightful commentary.

Am really touched by this text..It’s well with him.

Two thumbs up!

God, your headline scared me – I thought we’d lost him!

Looks like a beautiful article, thank you for posting it.

Thanks CB, this has to be the most awe inspiring interview I have ever read. I am so touched. It made me think. That quote about death was beautiful. Made me think of death in a different way.

What an inspiring man. And a good read (the Esquire article, really touching). Thank you for your story about it.

Wonderful that they are creating a speech box that will have his voice. He deserves this. He also deserves to live well beyond so many of the self-distructive brainless types in Hollywood today, but he seems at peace if he doesn’t.

Wow. I almost started crying at my desk at work. What a wonderful man. The part about Gene Siskel had me damn near bawling

I just want to cry. i love to talk i love the fact the we humans can talk. to not be able to to and hold it together shows the true measure of a man he’s amazing

Thank you CB for sharing this. I don’t read Esquire so I never would have read this if not for you. I loved starting my day with this.

Yes, thank you CB for posting this and for sharing your beautiful sentiments! There is definitely something transcendent about this. The writer for Esquire did a fantastic job in honoring Mr. Ebert like this.

Thank you CB. I was floored by your post even before I read the article.

I am so glad you posted this. Thank you.

Thank you for posting this. I love what he said about making yourself and others un/happy.

I started to cry when reading this. I knew nothing about Ebert’s health struggles, but plan on starting to read his blog. Thanks for showcasing such a strong man.